Introduction

Before learning about how an entire network of controllers can seamlessly communicate without interruption or conflicts, it is important to understand the basics of sending a data over a single wire (or twisted pair of wires).

When we refer to "data" in this context, we are really talking about binary numbers. Computers and electronics are really only capable of storing and processing binary numbers. So how can it be that you are reading these words on a screen with different shapes and colors if computers only understand binary numbers? Well, everything you interact with on a digital electronic device is represented by a binary number. For example, if you look up an ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange) chart, you'll see that every letter and symbol on your keyboard has a corresponding binary number. Images and colors are also stored as an array of binary numbers that can be sent to a screen where they are turned into colors and shapes that humans recognize.

The same is true for one controller on a network sending and receiving information to and from other controllers on that network. The data being shared is nothing more than a series of binary numbers that represent something real.

1's and 0's

Okay, so now that we know all of the information sent between controllers is comprised of only two numbers, 1 and 0, we will now learn how a single wire can be used to send a stream of these numbers.

You are probably thinking that CAN physical layers are twisted pairs of wire, not a single wire. When we discuss the physical layer later, you will see that this doesn't change any of the theory and there are actually low-speed networks that use a single wire. The twisted pair of wires are actually simultaneously sending the same signals, so they are really acting as a single wire.

Going back to basic electronics, we can remember that there are three properties of a circuit that we can easily measure. Voltage, Current, and Resistance. All three of these properties are also related to each other, following Ohm's Law of Voltage = Current X Resistance.

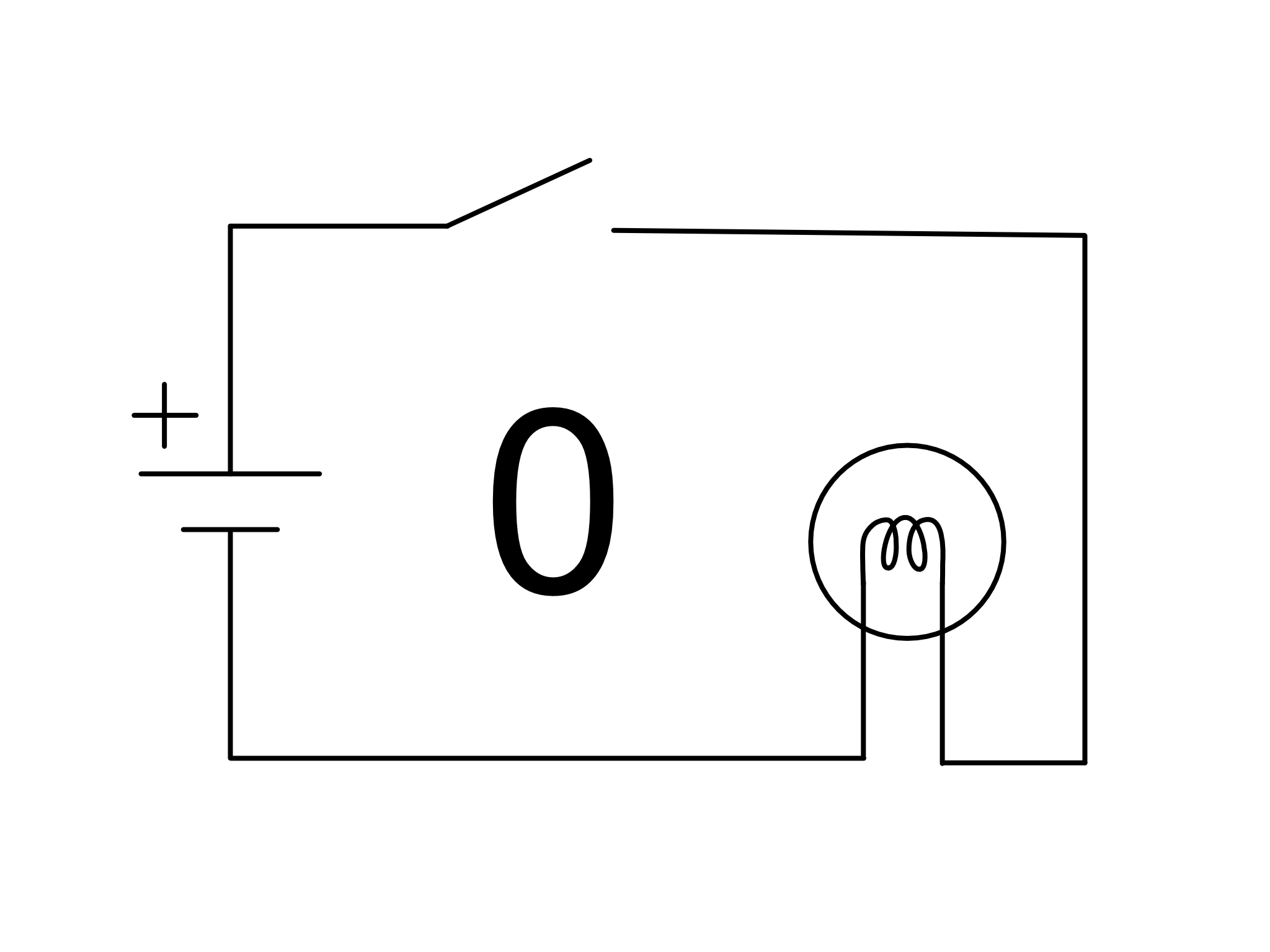

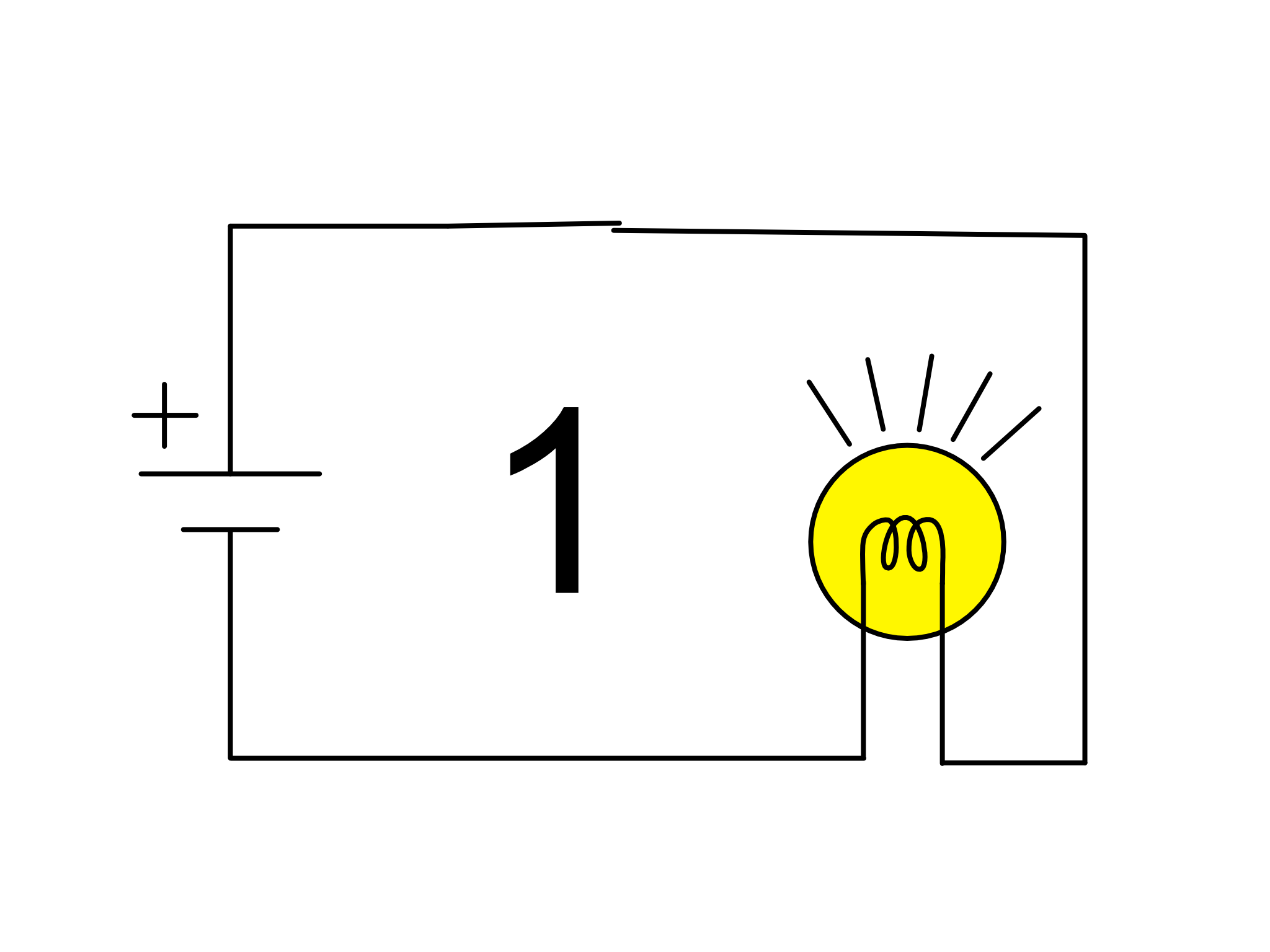

Imagine a simple circuit with a battery, switch, and lamp. We know that closing the switch raises the voltage of the rest of the circuit and current begins to flow through the lamp. The resistance of the lamp drops the voltage back to zero, satisfying Ohm's Law. This silly example of a simple circuit is all we fundamentally need to transmit data.

The example circuit has two states: switch open and switch closed. With the switch open, the voltage at any point after the switch is zero. When the switch is closed, the "downstream" voltage rises to the same voltage as the battery. There we have our two states, or two binary numbers. Switch open = 0 and switch closed = 1. But which of the three easily measured electrical properties should we use to define a binary 1 or binary 0?

Which Electrical Property Do We Actually Measure?

Lets start with resistance. Does the resistance of the circuit change when the switch is closed? No. Resistance won't work because it is a property of the physical parts of the circuit. A mathematical constant. In order to send two distinct binary numbers, we need something that changes. Resistance is out.

What about current? The current does change when the switch is closed, but lets think about some implications surrounding current. Current is flow, or electrical 'movement' to relate it to physics. Once motion is involved, work is being done, and work takes energy.

Energy and motion have dynamic effects surrounding the storage and dissipation of energy, which tend to have negative effects when we are trying to speed things up. Think about how it's easy to slowly wade through knee-deep water, but try to run and you'll find that the amount of energy required for each step is tremendous compared to running on dry land. If we are talking about transmitting data as quickly as possible with the least amount of energy, we certainly shouldn't be running through water, or even running at all. Current is out.

The only thing left is voltage. This is our winner. Although current and resistance are still present, varying the voltage is the easiest way to measure two distinct states of a single wire without expending excess energy. By increasing the amount of resistance and consequently decreasing the amount of current as much as possible, a change in voltage can happen nearly instantaneously and with very little energy consumption. Think back to the running through water example above, using voltage to define our states is like tapping your foot on the ground.

Voltage to Binary

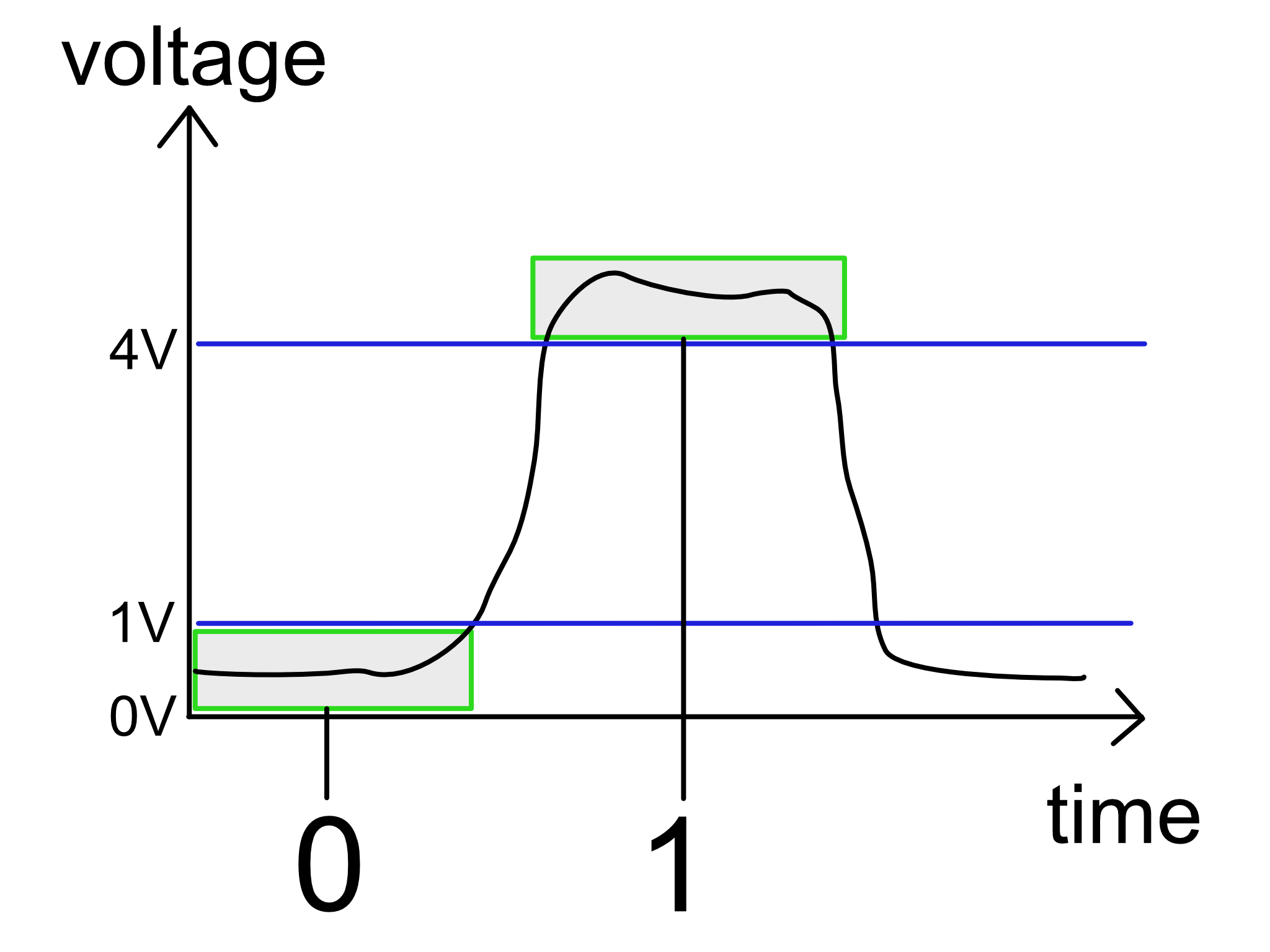

So now that we know voltage is the preferred electrical property to represent our 1's and 0's, it should be pretty simple to determine the binary state of our communication wire. We can say that if the voltage measured on the wire is below a certain value, it's considered a 0. If the voltage is above a certain value, it's considered a 1.

For example, we can say that if the voltage measured is below +1V, then we'll consider that a logical 0. If the voltage measured is above +4V, then we'll consider that a logical 1.

Each protocol defines these threshold voltages and tolerances differently. For now it is just important to understand that the voltage fluctuates between two different values and the controller is able to measure the voltage at a given time and assign it a logical value 1 or 0 based on the measured voltage.

Timing

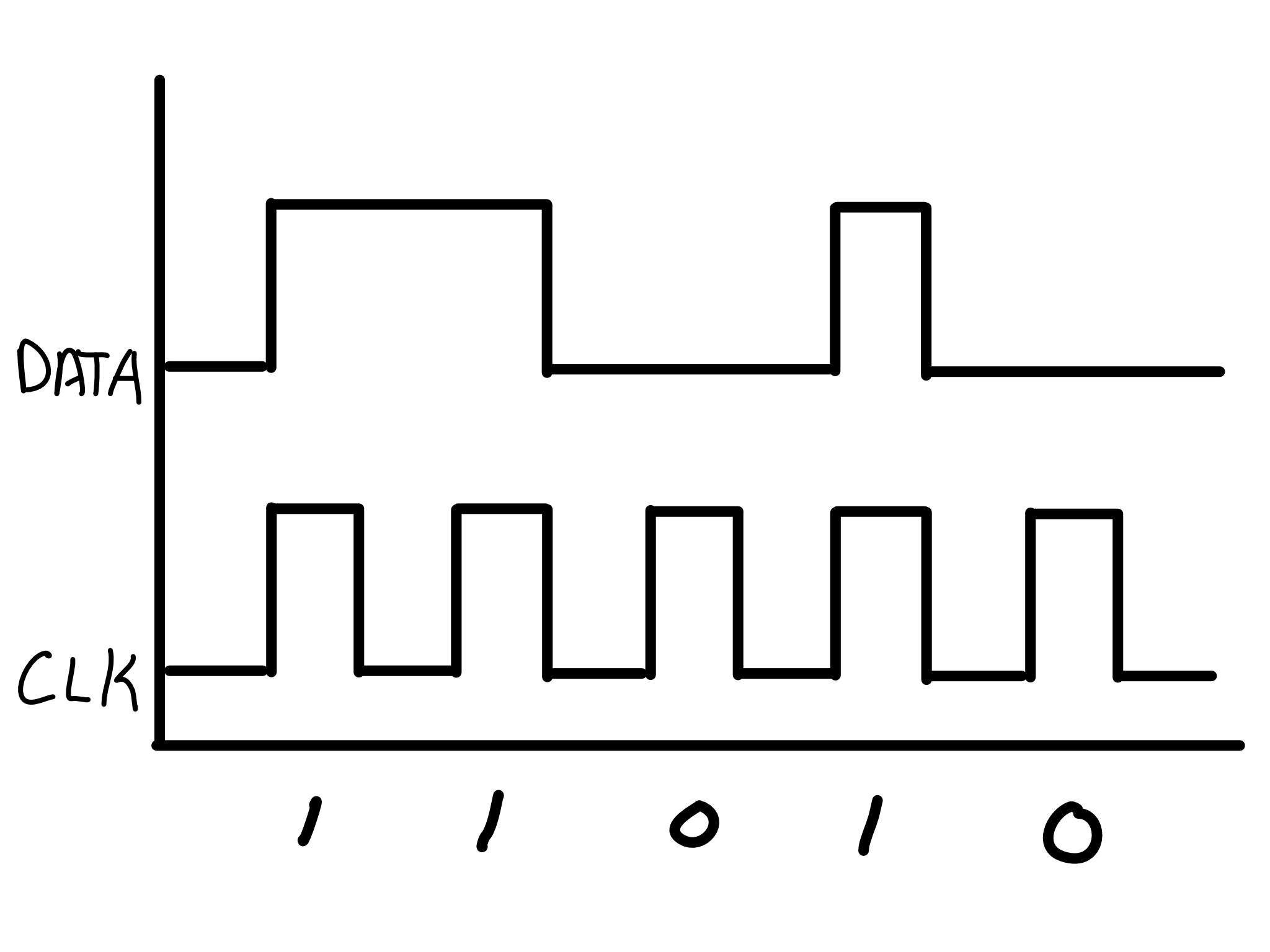

Just changing the voltage on a wire isn't enough to send data from one controller to another. All senders and receivers need to know how fast the bits are being sent by one controller so they can be read by the receiving controller at exactly the right time. For example, if we wanted to send two '1' bits in a row, the receiver could read that voltage change once instead of twice and get the wrong value. The receiver needs a way to know that the voltage it measured on the data wire should have been sampled twice instead of once.

One method is to use a separate wire, called a clock, that just switches on and off at a fixed rate so that both controllers know exactly when one bit ends and another one begins. Every time the clock wire changes its voltage, the data wire voltage is measured and turned into a 1 or 0.

But how do we remove the clock wire so we can send data with just a single wire? It can be done, but it requires all controllers to know how fast they should send outgoing bits and read incoming bits. This is referred to as the baud rate. Baud rate is the rate at which bits are sent. So if the network baud rate is 125k, that means that 125,000 bits can be sent in one second. Serial data communication protocols can have many different baud rates, however, all the devices on a single network must all use the same baud rate. So now, instead of relying on a clock wire to know when to read each incoming bit, each controller has it's own clock that switches on and off at the same rate as the incoming bits.

Synchronization

Assuming all controllers know the baud rate, all that is left to do is synchronize everyone's individual clocks so that they all start reading the bits at the same time. This can be done by periodically transmitting a special combination of bits that is recognized as a timing signal. That combination of bits will reset the receiver's individual clock to start its cycle at the same time as the transmitter's clock. This can be done at the start of every transmission and then again periodically to ensure the sender and reciever's clocks stay in sync. The only catch is that the timing signal needs to be unique and cannot be confused with regular data transmission.